The Incognito Author

A previously unpublished piece, circa 2012. A new regular essay will be up soon!

Paul Auster died yesterday. I wanted to share a brief essay I pitched to NPR’s All Things Considered that never aired that included a funny memory I have of the author.

For a while, I've been hearing a lot of chatter about my first humor book How Not to Read: Harnessing the Power of a Literature-Free Life. No, I don't mean that I've been reading book reviews on Goodreads or the twisted rantings of my internet stalker. I've been hearing the hype (or underwhelmed sighs) about my book firsthand. I've been listening to customers from my semi-incognito perch behind the counter of an independent bookstore.

To all writers who want to know what people really think about their work, I can't recommend working as an incognito author-bookseller enough.

With a title like How Not to Read, I expected some vitriol from customers who misunderstood the concept. I thought 18 to 35-year-olds would especially love it but for a generation defined by its penchant for irony, we sure do know how to not take a joke. For the most part, people much younger than I am are the ones most offended. I hear little children with pained, screechy voices asking their mothers: "Why would someone write this?" to which the mothers reply "I don't know sweetie," as if informing the kids about death for the first time. Another favorite is hearing a sixteen-year-old say "who would do this?" over and over with the type of outrage reserved only for political candidates who claim Barack Obama wasn't born in the United States. The answer is "I would" but I keep it to myself. I want to see how far it goes. I keep waiting for someone to impulsively tear the book to shreds. That's how mad some people sound.

But most people who read a lot, get it. They come into the store, they laugh at the cover, the very concept of a guide to helping people read less is funny! It tickles them. They flip through the book and laugh and laugh and laugh, then put the book down and promptly leave the store without buying it.

"Wait!" I yell, "What didn't sell you on this book?" (I'm careful not to reveal who I am at these moments).

"Well," the person responds, "I'm just not in the mood to laugh right now." Not in the mood… to laugh? I wouldn't want to see this person at a restaurant: the waiter comes to the table and says "How were your appetizers?" and this person responds: "you know, food just isn't my thing…" I thought everyone was in the mood to laugh, but this was one of my many misconceptions about readers before working in a bookstore.

I've been working in this store for about a year, during which time I've spent countless hours talking about my own book, trying my hardest not to tell every person who enters the store that I wrote it lest I lose my ability to observe the impartial reaction of customers. Tip to published writers, though: if you can hand your own book to a customer and say "this is my book and you should buy it," people usually do. Most of the time they buy the book because they're excited to tell people they've met you, and sometimes they buy the book because you made it very awkward for them to leave the store without doing so. Keep eye-contact. Don't show fear. Always be closing.

Deciding when and when not to be the incognito author has many humbling benefits. Though the big lesson it teaches you most first-time authors are already know: the number one review of your book won't be a petulant rant. Your number one review will be silence. People will walk in, they'll read ten pages of your book, and without so much as an indecisive "hmm" they will disregard your book forever. As Oscar Wilde said: “There is only one thing worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” I'll take the petulant rant any day over nothing.

At the risk of this essay becoming like If on a winter’s night a traveler, the more I sell my book in secret, the more my real life mimics a Paul Auster-y meta-literary detective novel where I keep spying on people to figure out who will like the author (me) the most. It keeps getting weirder and weirder. People who have read the book now come in quoting a particular joke they didn’t like, then stand staring at me without laughing. I laugh uncomfortably to break the tension, but they refuse to crack a smile. Sometimes, I picture the future author version of me walking into the store while Current Dan is working as a bookseller. I see Future Me looking at the book nostalgically and saying “eh, this wasn’t my best!” then leaving me behind the counter alone to cope with what just happened.

The closest story I have to this Auster-esque fantasy is when the real-life Paul Auster came into the store the day of the book’s release. He leaned on the counter, aviators still on, and said: "How Not to Read, huh?" He was laughing! Laughing at the very idea of my book’s existence. Paul Auster gets it.

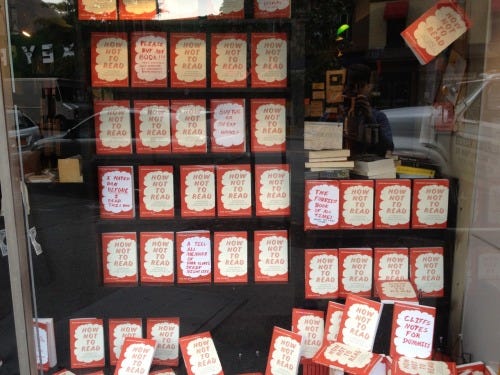

I took a sharp breath in. The owners of the store were so excited about my book that they gave me the entire front window for a day to promote the book. The same bright red cover in 8 by 8 rows and columns. I was suddenly embarrassed that I had published a book at all, and frightened that my literary hero might actually page through it in front of me.

Then I remembered I had something to tell him.

“Paul!” I watched as he took off his sunglasses. I had his full attention. “I originally had a section in this book that parodied the New York Trilogy, and you yourself were in it," I said excitedly. Then, before I could stop myself, I saw the words pour out of my mouth while my brain screamed ‘DAN. Don’t!’ I let this out:

“The editor suggested we cut it because no one would get the reference."

I watched Paul grimace. He pushed himself off the counter and put his aviators back on. “And that's why you never listen to editors!" he announced before abruptly walking out the door.

If I have any advice for a writer, it is this: spend ten years as an editor for other people while you work on your own stuff. You’ll get used to looking at words on paper as malleable and in need of repair. Maybe after a decade of cold perusals through the work of a stranger, you'll be able to whittle down your own work into a readable form. After that, spend another decade selling your published books in person at an indie bookstore. Twenty years in, you won't take anything personally. You'll be so used to rejection and snide comments, you’ll be impervious to criticism.

My only other advice is if you meet your hero during any stage of your literary development, don’t tell him he was cut from your book because he isn’t famous enough.

rest in peace, paul auster. what a great memory to have.